The xz backdoor from a Security Engineer persepective

Yet another supply chain attack

As you probably already heard, the xz package got compromised.

The package was used as entrypoint to inject malicious code in sshd, altering the authentication flow. This forged vulnerability is now known as CVE-2024-3094.

Looks like the injected code takes the payload from a specific key and execute it.

This is probably a full fledged operation due to its methodology and duration but I’m not the right guy to talk about OpSec and Threat Actors attributions. Check the Resources section for additional links.

The situation doesn’t look too good so I’m trying to write this blogpost as a summary.

I don’t want to address the technical aspect of the compromission but I want to look at the issue from the perspective of a Security Engineer, summarizing what went wrong and trying to find a remediation.

1 Timeline

2023:

- A new maintainer shows up in the

xzproject

- A new maintainer shows up in the

29 Mar 2024:

Andres Freund sent an email to the oss-security mailing list regarding a backdoor in

xz/liblzma. He was optimizing his infrastructure and found that ssh was suspiciously slow. Some debug later he found the issue was likely caused by the backdoor. The initial analysis was performed with the help of Florian Weimer.Impacted distros are starting to ship patches to downgrade the xz version (more on that later)

30 Mar 2024:

GitHub blocked access to the repostiory and blocked the account of both the xz maintainers, an updated code is available here

An official statement was released by the project maintainer

31 Mar 2024:

- potential killswitch identified, take that as a grain of salt

2 Impacted components

The extent of this breach is still unkown, but here is a (partial) list of components shipping the known malicious version of xz:

Distributions:

- Arch

- Debian Sid

- Gentoo

- Fedora 40

- Manjaro Testing

- Parabola

- NixOS Unstable

- Slackware

- SUSE Tumbleweed

- Kali Linux

The backdoored package is also contained in the repositories of the following package managers:

- Homebrew

- MacPorts

- pkgsrc

At the moment we know that there are checks in the backdoor to target Linux instances and only x86_64/amd64 builds so the real number could be downsized, but since the entire situation is unclear I would not reccommend to keep a compromised package on your system.

3 Considerations

3.1 The GitHub Behavior

The reasons behind the xz repositories lockdown are still a mistery to me, especially knowing that with the source code available additional anaysis on the backdoor could be performed.

Blocking access to the source code is something that will delay further results, that is honestly really bad for time-critical situation like this one. An updated mirror is available here

3.2 The downgrades

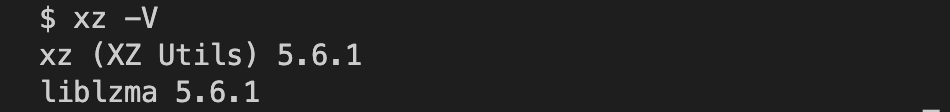

The patch strategy for basically everyone was to force a downgrade from the 5.6.0-5.6.1 to another version.

Some (homebrew, for example), forced the downgrade to 5.4.6.

This looks interesting because for sure we know there is a backdoor on that (5.6.0-5.6.1) versions, but we also know that the attacker has been working on the repository for over two years.

The 5.4.6 version is also builded by the attacker and honestly wouldn’t trust it much.

4 How to prevent this issue?

As I said at the beginning of the post, I don’t want to go too deep into the technical analysis of the backdoor, for two main reasons: with the sourcecode locked and only an archive available the informations are incomplete and I really don’t want to reverse the xz binary.

Also, and this is the more important reasons, people more knowledgeable than me on Threat Actors behaviors are already on it.

I will just link their posts once are ready, so make sure to check the Resources section below.

One thing I can do here is showing the point of view of a Security Engineer on the issue, how I would mitigate the problem and what steps went wrong.

4.1 Trust issues

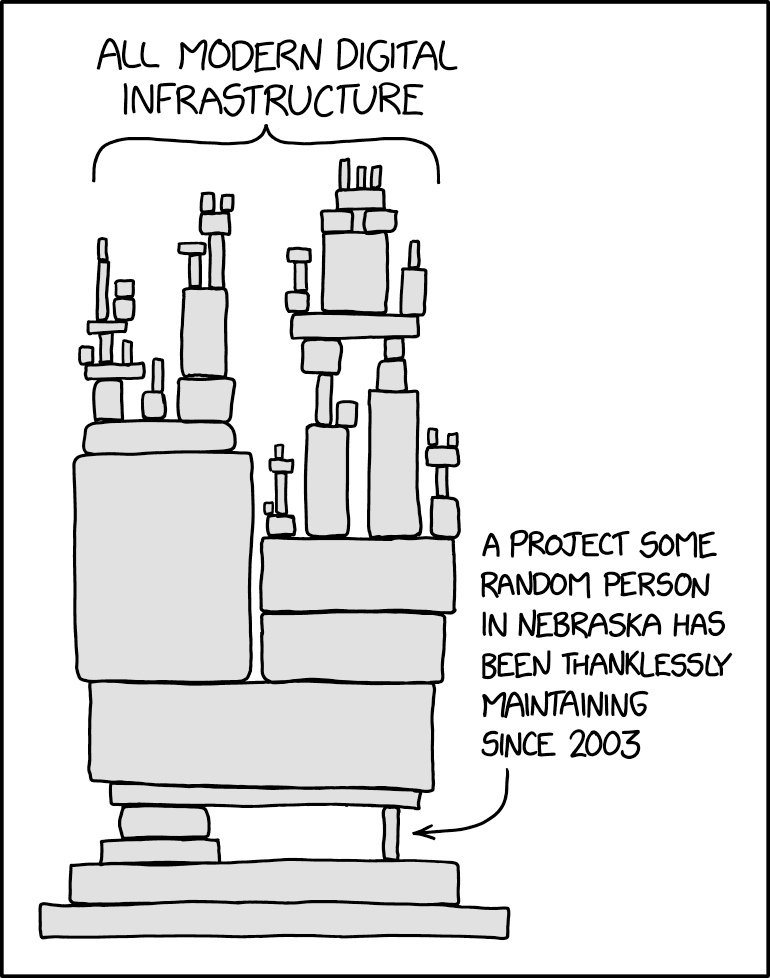

xz is a software mainteined (up until 2023) by 1 single guy. Later another maintainer joined but unfortunately for us, it was the same guy pushing the backdoor to upstream.

This crashes against the fact that xz is an incredibly popular package available in a lot of distributions and being a dependency of many softwares.

This was likely seen by the attacker as a gold mine since it was easy to get the role of maintainer of the project and push the malicious code.

Since you are using a thirdy-part source for your supply chain, you have to trust someone at one point or another. When talking about supply chain security the reccomendations are always the same: pin the hashes and use signature verification. This will work as long as you have scenarios like a malicious attacker compromising the dependency CICD and pushing a malicious build, account compromissions etc.

But what can you do if all of a sudden, trusted maintainers goes rogue?

As a standard user, unless you want (and are able to) code review every single commit from every single piece of software your OS interact with: pretty much nothing.

On the other hand, developers and repository owners should really increase controls on their supply chain and include strict metrics to exclude high risk packages. One of the biggest gimmicks of Open Source security is people beliving that since the source code is available the code magically became safe.

One critical factor often overlooked is the assumption that having access to the source code automatically translates into a larger pool of eyes scrutinizing it for vulnerabilities.

The effectiveness of this review process depends on the level of community engagement and the expertise of those inspecting the code, and usually is not much at all. Many projects receive minimal attention from developers, with only a handful of individuals actively contributing or reviewing code changes. As a result, vulnerabilities (intentional or not) may go unnoticed for extended periods, posing significant security risks to users.

Every time a discussion like that appears I always remember the InfosectCBR’s “Month of Kali” where Silvio Cesare spent a month popping vulnerabilities on Kali Linux software.

But which factors could contribute on minimizing the risks?

4.2 GitHub Stats

Just to be clear from the beginning: No, you can’t trust this kind of metrics.

There is an hidden market of buying and selling GitHub stats like stars, forks etc. You can read a nice article here: https://dagster.io/blog/fake-stars

4.3 Community Engagement

Evaluate the size and engagement of the community surrounding the project.

A large and active community can provide additional eyes for reviewing code, reporting bugs, and addressing security issues promptly. xz/liblzma had litterally 2 maintainers and one was the malicious actor.

4.4 Funding and Support

Consider whether the project receives financial support or sponsorship from reputable organizations. Projects with dedicated funding tend to have more resources available for security audits and ongoing maintenance. And also are less likely to be completely abandoned.

4.5 SDLC

A good portion of the evaluation should also focus on the SDLC to e ensure security (and quality in general) gates are correcly implemented, approvals on PRs are mandatory and there are healthy practices in place to prevent one single contributor to push malicious code without approval.

Also take in considerations that we are humans, and we make errors. Passing a code review doesn’t mean the code is safe, as I said before: there is no real solution, just ways to decrease the probablity for the bad stuff to happen.

4.6 Enterprise vs Individual

This is a controversial topic because there are projects that are maintained by individuals that are well structured but usually relying on (large) enterprise projects will ensure their SDLC best practices are followed, money are keeping the project alive, and a big company is less likely to go all in and backdoor their project on purpose. Again, this just increases the probablity, don’t take it for granted ;)

4.7 Recursive controls

The project you are including will probably also have dependencies, make sure the same scrutiny is applied by the project maintainers on their supply chain to avoid indirect compromission.

5 Conclusion

The xz backdoor is yet another case of supply chain hijacking, but this time with way more complexity and effort behind it.

We shound’t blame the current maintainer or the Open Source software: issues like that (intentional or not) are mostly unpatchable because they leverage the human factor that is inreplaceable.

On the other hand we can follow some best practices in picking software to integrate inside our repositories to reduce the chance of this from happening.

6 Resources

- OSS-Security List: https://www.openwall.com/lists/oss-security/2024/03/29/4

- Comprehensive timeline: https://boehs.org/node/everything-i-know-about-the-xz-backdoor

- Compromise link roundup: https://shellsharks.com/xz-compromise-link-roundup

- Obfuscation Analysis: https://gynvael.coldwind.pl/?lang=en&id=782

- Backdoor Analysis: https://gist.github.com/smx-smx/a6112d54777845d389bd7126d6e9f504

- Additional info: https://bsky.app/profile/filippo.abyssdomain.expert/post/3kowjkx2njy2b

- Visualized timeline: https://infosec.exchange/@fr0gger/112189232773640259